|

| Miami liquor raid 1925 Florida State Archives |

By Jane Feehan

Women played a part (or tried to) in rum-running from the Bahamas to South Florida during Prohibition (1920-1933).

Gloria de Cesares, 29, reportedly born in Argentina and educated in England, founded the Gloria Steamship Company to run her illicit enterprise. An accomplished navigator, she bought a British five-masted schooner, the General Serret, and loaded it with liquor for a trip to the Bahamas. She didn’t get far. The cargo of the General Serret was discovered, perhaps by a tip from its unhappy captain, before the ship left port, ending de Cesares’ rum-running career.

“Spanish Marie” Waites was far more successful; she headed up a “rum-running empire” after her husband was killed during one murky mission. Some say he was shot, others say he drowned after Marie pushed him overboard.

The tall, darkly attractive woman “strutted with a revolver strapped to her waist, a big knife stuck in her belt and a red bandana tied round her head.” Spanish Marie commanded a fleet of 15 to 20 radio-equipped speed boats that outran U.S. Coast Guard vessels for years. She delivered rum from the Florida Keys to Palm Beach. In 1928 she was caught unloading liquor with the help of her crew in Coconut Grove. A $500 bail was posted then raised to $3,000 when she failed to appear in court. She disappeared leaving no other traces to history.

|

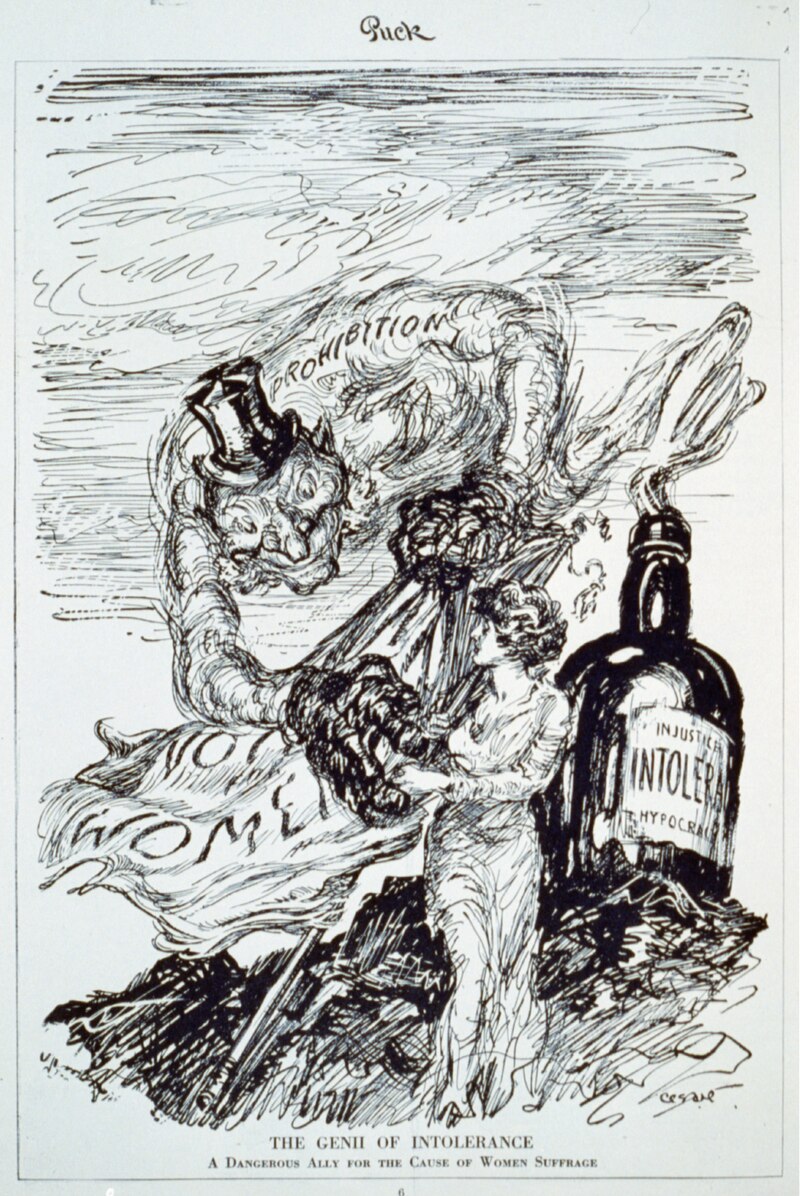

| By Oscar E Cesare, Puck Magazine 1915 Criticizing alliance of women's suffragettes and Prohibition advocates |

Gertrude Lythgoe, a Californian who went to New York and then worked for a London liquor distributor, became known as the “Bahama Queen” for her efforts. At the behest of her employer, she set up shop in Nassau where she became the only woman to hold a wholesale liquor license. Lythgoe’s reputation as a comely, well-read, tough (she threatened to shoot one of her critics), liquor distributor grew. She later wrote about her exploits in Bahama Queen: the Autobiography of Gertrude “Cleo” Lythgoe.

Tags: Prohibition, women's history, Florida history

Sources:

Behr, Edward. Prohibition:

Thirteen Years That Changed America. New York: Arcade Publishing, 1996.

Ling, Sally J. Run the

Rum In: South Florida During Prohibition. Charleston: History Press, 2007

Willoughby, Malcom F. Rum

War at Sea. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1964.