By Jane Feehan

|

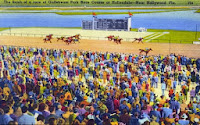

| Gulfstream Park 1948 Florida State Archives |

It was estimated that 2,000 bookie joints operated in the Greater Miami area (including Fort Lauderdale) in 1948-49.

“Wig wag” men helped ensure success of the popular but illegal gambling industry.

These men traveled the country from track to track to communicate through hand signals the new line, or post race odds, while horses ran. Signals included smoothing hair, raising arms with fingers outstretched, running arms down their sides, patting their heads, scratching and more. Wig wags, brightly attired so they could be picked out in a crowd in front of the grandstand, were observed by scanners, or people located about a half-mile away.

In Miami, scanners were situated at a large two-story house at 7701 Bird Road. They used powerful military binoculars to track the changing odds. Changing odds were important to bookies; it insured that favorable odds would not be beaten down by bets going through machines legally at the track.

The house on Bird Road (long gone and now part of a highway) was the nerve center for Miami’s bookie industry. During the 40s, most bookies operated in Miami under mob-run and intentionally misnamed Continental Press Service. Press services needed telegraph and telephone banks.

Investigating reporters in 1948 visited the house where they found a “motherly-looking woman” on the first floor, knitting. The clicking of her needles ostensibly drowned out telegraph tapping on the floor above. (Phones had been pulled out after prior police investigations.) Bookies also used short wave radio or “mobile automobile radio” from a locked car to hear a race in progress. A microphone would be suspended beneath a car located near the track.

Investigating reporters in 1948 visited the house where they found a “motherly-looking woman” on the first floor, knitting. The clicking of her needles ostensibly drowned out telegraph tapping on the floor above. (Phones had been pulled out after prior police investigations.) Bookies also used short wave radio or “mobile automobile radio” from a locked car to hear a race in progress. A microphone would be suspended beneath a car located near the track.

The most favorable swindles were those involving out-of-state locations with lag times in telegraph communication. Last minute odds—whittling odds—was the lifeblood of bookie operations; without them, 95 percent of their business would disappear. In 1948, bookies raked in between $250 million to $300 million from Hialeah, Tropical Park, and Gulfstream race parks in South Florida, and Sunshine Park in Tampa while about $98 million went through the same tracks legally.

Eight percent of legal betting revenues went to the state in taxes. Five percent was divided among Florida’s 67 counties where it sometimes subsidized an entire county government. The remaining three percent went to an old age assistance fund matched by federal money. Illegal off track betting probably cheated the state out of $10 million a year then. Tax losses served as some of the fodder in the campaign against illegal gambling in the late 1940s. Arrests of wig wag men were routine by 1949.

Betting continues to be big business in the Sunshine State, but today it’s predominantly legal. Gambling revenues from six South Florida state-operated casinos (not Seminole establishments) jumped more than 12 percent in 2013 netting the state $162 million in taxes; the national average was a 4.8 percent increase. Copyright © 2013. All rights reserved. Jane Feehan.

Sources:

Miami News, Dec. 12, 1948

Miami News, Dec. 13, 1948

Miami News, Dec. 14, 1948

Miami News, March 8, 1949

Sun-Sentinel, May 7, 2013

Tags: Gambling history, racetrack gambling in the 1940s, Continental Press service, wig wag men, film researcher